Let’s talk about usage-based pricing for a bit (I’m going to use “UBP” as a shorthand because I imagine I’m going to repeat that phrase over and over again here).

UBP is a topic that earns a lot of attention in organizations that are either A) doing it, or B) thinking about doing it. It makes sense: Usage-based pricing is one of those technical problems that has a very direct and tangible impact on revenues for a business. You screw up building a usage-based pricing system, and you’re either going to leave money on the table, or overcharge (and piss off) your customers (and then call on your data team to unravel a whole web of events histories in your data warehouse to reconcile everything).

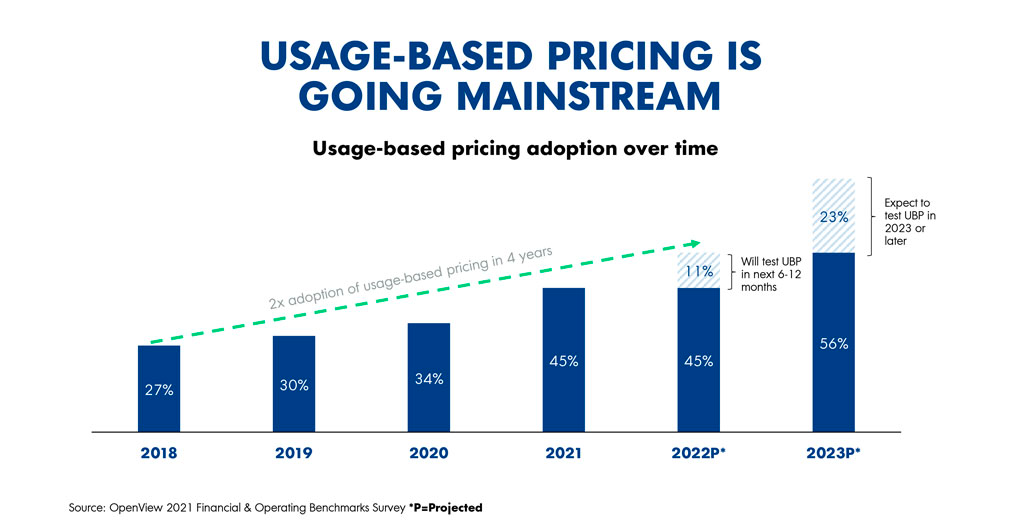

UBP is pretty hot right now. Just google “usage based billing” or “usage based pricing” and you’ll see blog headlines like “The future of software is usage based pricing” or “Inside the rapid rise of usage-based pricing.” OpenView asserts that UBP adoption has doubled in the last 4 years and probably will again in a couple years.

A lot of companies that do UBP want to buy a SaaS tool to handle it, and there are plenty of great options for UBP SaaS: Amberflo.io, Metronome and newcomer m3ter come to mind as API-first usage-based billing platforms. But why buy UBP off the shelf? Well, because it’s relatively proven, a pretty narrow use case, serverless, and when it comes to how your business actually collects, you’re willing to spend a bit more, right??

I also think that many companies generally (and maybe unreasonably) assume that buying UBP off the shelf will just be cheaper, faster, and safer than building it internally.

This is how the build vs. buy decision at nearly every software company goes:

The Engineering team wants to build UBP themselves, because they don’t want to be constrained by the limits of a particular SaaS product, and because, given the time and resources, they could probably (definitely) build something more fit for purpose for their company’s existing tech stack and pricing models.

The Execs worry that Engineering will underestimate the effort involved, overspend, and over-tinker. Or they assume that whatever Engineering might build won’t be that much better than an off-the-shelf product so as to justify the time and cost to build it.

Also, because UBP involves data - and special scrutiny on quality and governance as it’s related to revenue - they worry about managing a cross-functional effort involving the data team, the developers, finance, and RevOps.

So they make the choice to buy instead of build. And like most companies that don’t trust their devs 😉, they buy something that mostly kinda works.

But then they start using it, and as with nearly all SaaS products, the shininess begins to fade. The SaaS pitch starts to get exposed, and the company realizes that the 95/5 “use case coverage” they were promised by an overzealous AE is more like 80/20. Which is fine for most.

But maybe the tool they bought also can’t handle that critical requirement they now need, and the CTO and CFO wonder why Engineering didn’t properly vet this use case (likely answer: Product just threw it over the fence last week).

It's the archetypal story of build versus buy, especially when it comes to critical processes like usage-based pricing. But we think that story can change.

Build vs plus Buy: The best of both worlds

In a traditional approach, “build” and “buy” each have their own list of pros and cons.

“Build” usually means

- more flexibility (maybe),

- more power (maybe),

- more control,

- more maintenance,

- more time to implement (probably),

- and more fights between development and data engineers (definitely).

“Buy” usually means

- faster execution time,

- pre-built integrations (maybe),

- lower upfront costs (maybe),

- less flexibility (probably),

- less control,

- and more time dealing with SaaS support chatbots (absolutely).

When you really start to break it down, though, the build vs. buy argument for UBP isn’t really any different from that for any other as-a-service tool. You’re paying for an abstraction: A simplification of the undifferentiated bits so you can focus on writing differentiated code.

But what’s the tradeoff? The reality for most considering a UBP SaaS purchase is that the primary value lies in the abstraction of infrastructure: A system that can process events, apply aggregations with low- or no-code tools, process rating logic, and ship an invoice with a Stripe integration. It’s up to developers and revops to define and implement the logic, and hope that the SaaS tool can handle current and future use cases.

But are there other sets of tools that can provide the same abstraction of infrastructure while still offering the benefits of “build”, namely the power and flexibility to create that pricing logic that perfectly suits your business now and in the future?

Here’s what we think: With the advent of realtime and streaming analytics platforms (like Tinybird, but including others) that are bundling a lot of the infrastructure that a UBP SaaS provides, the value of certain UBP SaaS products may diminish, especially for customers who have a handle on implementing revenue logic in a language like SQL.

Now, I’m going to go ahead and anticipate an objection I think that many might have: Doesn’t using a realtime analytics tool just offload the SaaS purchase to a different tool stack? I guess so. But that’s not really the point.

The point is that what you want in a usage-based pricing tool is something that will eliminate the complexity of deployment (by providing infrastructure and tooling) while still allowing some control over the business logic.

Buying an off-the-shelf SaaS product is one option, but if you decided to build usage-based pricing in Tinybird (for example), you’d get the same infrastructure abstractions as with an off-the-shelf tool, and your control would only be limited by the boundaries of SQL. Could you say the same for SaaS?